My mother’s first visit to the United States coincided with a light snowfall, which we encountered while traveling Upstate. As a visitor from the tropics, she was immediately intrigued by the accumulation of the material on the ground, calling it “ice.” I tried my best to explain to her the difference between snow and ice and that:

Ice Is Not Snow: A transcript of several long-distance telephone conversations between my mother and me

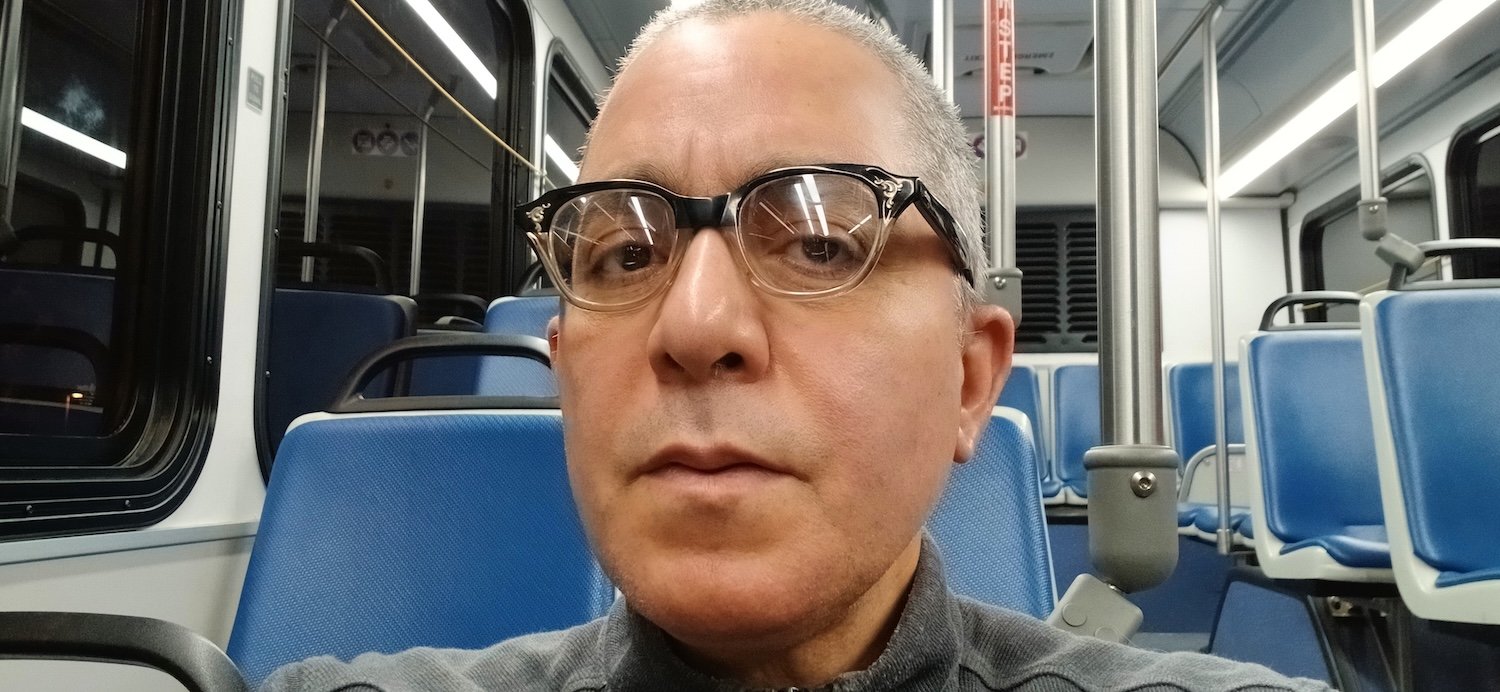

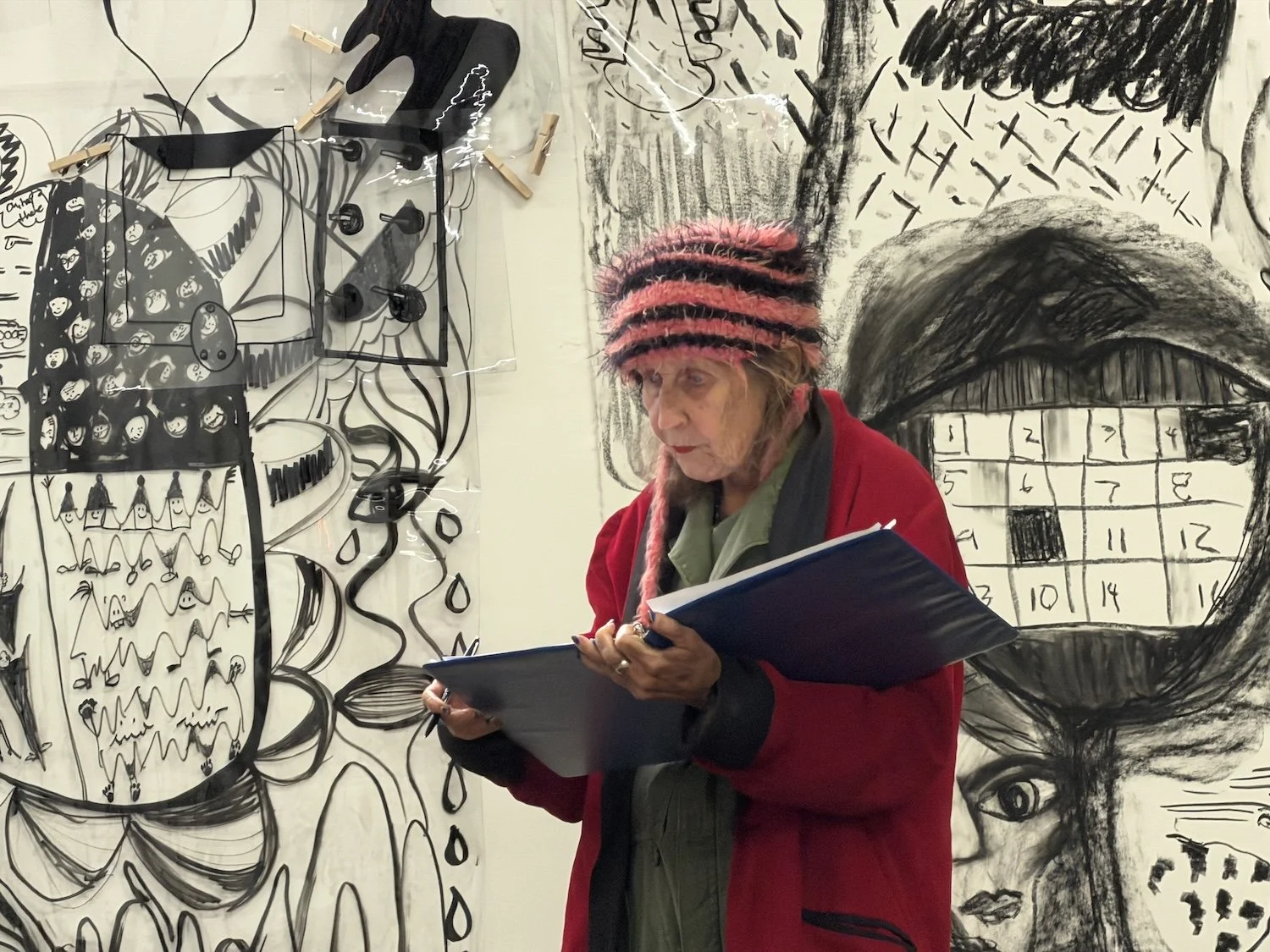

Nicolás Dumit Estévez & Margot Raful

Nicolás Dumit Estévez: What was your experience like in New York City?

Margarita Raful: For me, it was a wonderful experience because I wasn't like other Dominicans who go dancing, sightseeing, and to nightclubs. I went to visit museums and important places that enriched me with a lot of knowledge, like my trip to the countryside. I really love nature, crops, and animals, and for me, it was a great to be able to appreciate so many beautiful things that I hadn't seen in a long time.

NDE: And why do you say that you hadn't seen beautiful things in a long time?

MR: Beautiful? Because I hadn't seen a beautiful crop like the one I saw in the countryside in New York. The crops here in the Dominican Republic are in small plots. There in New York, I saw crops of a different kind, full of dew and freshness. Here, you have to water plants a lot because the climate is very harsh, while there, since it's so cool, you don't have to water the plants, and they always stay very beautiful.

NDE: And what was your impression, Mami, when you arrived here in the City? How did you see everything. How did you perceive the space?

MR: Well, it was something I saw in my dreams exactly as it exists.

NDE: So, nothing surprised you? You didn't find anything…?

MR: No. Nothing surprised me. I visualized it that way, and that's how it was.

NDE: And how did you visualize it before?

MR: Before? Well, a town, a country with a lot of activity, with tall buildings, not like here where most houses are low, and the people there are very hardworking, trying to improve themselves every day: some study, others work, others work and study; they lead a somewhat hectic life, but all triumphs come at a price.

NDE: Now that you say people live hectic lives, what do you think is the difference between life here in New York and there in the Dominican Republic?

MR: I don't know, the people who go to work there do so because they have a dream. Whether they're studying or working, some go there to stay and own a house, while others go to buy one here—it's the American Dream, as they say. Some go to work to buy a house here in the Dominican Republic and then retire, while others stay there.

NDE: You talk about the American Dream. I don't know how you perceive this. Do you think there's a dream in the Dominican Republic like the American Dream? The Dominican Dream?

MR: Well, I don't know. Sometimes people here dream of working, of living well, of having SUVs, cell phones, of competing with others because they want what others have. They like living like others live. Sometimes in the countryside there are young men who have fallen in love with the daughters of wealthy landowners. The women don’t pay attention to them because the men are poor, and maybe they work weeding, but they might go to the United States, work very hard to show those people who looked down on them because they were poor that they are also valuable. They come back from the United States with an SUV, a gold chain, rings, nice clothes, buy farms, and build them next to the land of the women’s parents, the ones who rejected them. You see that a lot.

NDE: Why do you think that is?

MR: Because some of these men feel looked down upon, being poor, with limited resources, and because they fall in love with the daughters of landowners and they are the one who clean other people's places. They feel sad because the women don’t reciprocate their feelings. The women’s parents tell them that they are not the right person for their daughters and that they don’t have the same educational or economic standing as their families.

NDE: Going back to my question, here we're talking about the American Dream, whether it's an illusion or a fallacy. Do you think there's a similar concept of a Dominican Dream in the Dominican Republic?

MR: No. I don't know. But I do know about the American Dream. Many Dominicans dream of leaving and succeeding.

NDE: What do you think the American Dream is here in the United States, without considering the Dominican context?

MR: I already explained it to you.

NDE: You're talking about Dominicans who wants to come here. I ask you, what does the American Dream mean to you?

MR: Ah! Dominicans dream that Americans are wealthy people who live well, and they dream of living like Americans.

NDE: And how does an American live according to that perception?

MR: By the book: they study, they work, and they get ahead. That's the American Dream I'm referring to.

NDE: Do you think your trip confirmed your perception of the American Dream? Do you think all Americans live like that?

MR: No.

NDE: What did you see?

MR: I think not all Americans live like that, because everywhere there are people who want to get ahead and others who don't, but most Americans live well.

NDE: On your trip, did you see poverty or anything that surprised you?

MR: Yes, I saw poverty. I saw people sleeping in the train station. I saw people sleeping on the ground. They are people who perhaps have mental health issues, traumas, don't want to work, or their minds aren't capable of leading a productive life, and they end up on the streets, at God's mercy.

NDE: Before you came to New York City, I told you about the idea I had of undertaking your visit to the United States as a life and art experience. What did you think of that?

MR: I thought it was very beautiful.

NDE: What is your perception of art? What is art to you?

MR: It's an artist's dream to capture an idea on a canvas, to sculpt or write…

NDE: Which places in the United States interested you the most, and why?

MR: The museums, which for me are full of unforgettable memories. I saw the mummies I dreamed of seeing someday, and I saw the work of Frida Kahlo, and Pepón Osorio.

NDE: Has this trip changed anything for you?

MR: It has. It allowed me to discover interesting places. You know, I practically live cloistered in my home, working. I had a lot of fun, saw my family, met your friends, and saw things I had never seen before.

NDE: And at a personal level, has anything changed?

MR: I feel like I can. That I can travel again. That the fear I had of leaving home is gone. I can do what others do because I'm alive. Because I have the desire to do it.

NDE: You managed to visit many places and people, what did you think of these?

MR: Where my brother lives, I felt like I was where I live, in Villa Progreso. Where you live, the place is very peaceful. I really liked the houses. I really like the decoration of your home.

NDE: If you could change something about the trip, what would it be? Or add something?

MR: Learn to navigate there. To get around like everyone else because I believe I can.

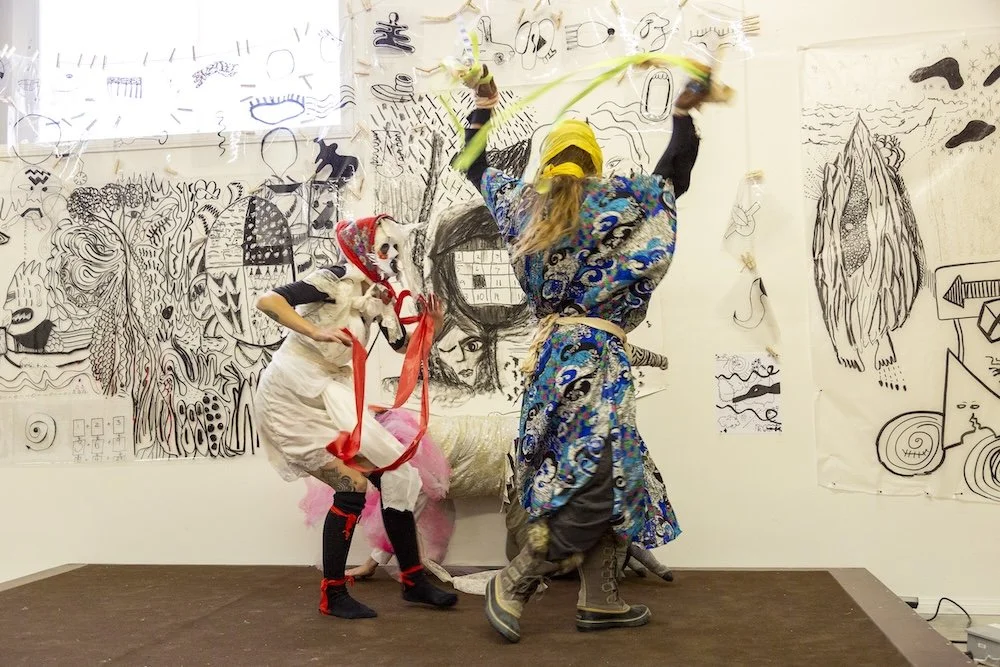

NDE: In the experience we shared, life and art intertwined in a space carved out of life itself, yet belonging to both life and art. What would you say about that? What role does art play in your life? Do you use art in your daily life?

MR: Yes, I use art. I use the art of cooking. I use the art of planting seeds. I have a lot of artistic talent.

NDE: Do you see cooking and planting as art?

MR: I see them as an obligation because I have to take care of my family, but I also see them as art because I enjoy them.

NDE: You say that planting is an art. What is art to you?

MR: Something that fills me with joy, that makes me happy.

NDE: Would you like to ask me a question?

MR: How do you see art?

NDE: Art is a tool. Most people have been taught that it's a product. When people think of art, what comes to mind is a painting, a sculpture, but they rarely think of art as a process or as a tool for learning to live, for learning to grow, for learning to relate to other people, and for learning to understand oneself and others. In our experience in New York City, I think that art made us aware of many of the moments we went through together with more attention.Is there anything you missed while you were here?

MR: No. I decided to remove that veil that binds me too tightly to what I left behind here in the Dominican Republic and to enjoy myself.

NDE: In other words, you let go.

MR: Yes. I let go.

NDE: We had previously worked together on several experiences and performances, for example, the one presented at Exit Art in 2001, for which I called you from thats space so you could send us a recipe by phone that we would prepare here in New York. Do you remember? You also helped me with an experience in 2007. You were the one who made the vestments for the Infant Jesus of Prague.

MR: Wait. I can't hear you…

NDE: Can you hear me?

MR: It's just that everything sounds far away…

NDE: The recipe you gave us over the phone. The drink with milk, condensed milk, and rum, Coquito.

MR: Yes.

NDE: At that time, you hadn't come to New York yet. When you were working on that performance at Exit Art, what were you thinking about the space you were sending your voice to over the phone? How did you imagine the other side?

MR: I don't know. I don't know how to tell you. Kind of strange.

NDE: Did any image come to mind, because you were calling and you knew your voice was being amplified through an audio system in New York, and that there was a group of people preparing the recipe you were dictating to us? Did you have an idea of what the space was like? Even a vague idea?

MR: Yes. I imagined it as a large place where many people were working.

NDE: We also worked on what was the incarnation—the embodiment? Is that the right word?

MR: Incarnation.

NDE: You know my Spanish has deteriorated because I've been here for almost twenty years. The incarnation of the Holy Infant of Prague. How did you process the fact that you were sewing the vestments for a saint?

MR: Very beautiful.

NDE: You also made the vestments for the people who participated in the Popemobile in 2001.

MR: Yes. The ones for the motorcycle taxi drivers.

NDE: Do you have any other questions for me?

MR: Not right now. Okay.

NDE: We've been talking about so many things. Do you remember when you used to ask me what I would do when I saw you dead? Why did you say that to me?

MR: Nonsense. I say it all the time, when I get angry. When you were mean to me, I would say, "I'd like you to see me dead in a casket. You'll die crying."

NDE: You told me I would see you with flowers, dead and cold.

MR: Nonsense.

NDE: Did you plant the onions Gail our neighbor, gave you from the farm in Upstate New York?

MR: Yes

NDE: Have they sprouted?

MR: No. I planted them yesterday.

NDE: Did you leave the tips sticking out?

MR: Yes. I planted the lettuce. I don't have much space left to plant anything.

NDE: And the Echinacea?

MR: Still.

NDE: Now that you've left, it's not so cold. It's gotten hot. Do you plan to come back to New York City? When would you do that

MR: I don't know. Someday. Oh! I was just arriving when I was hit by a car while walking. My feet were swollen. When I got to the church here, they told me they missed me a lot. They told me to stand up and they applauded me.

NDE: What do you plan to do with the photos from the trip? I sent you some by email. How was the trip back?

MR: The plane was shaking, and I was dying. They said there was turbulence.

NDE: You know, I dreamt that your neighbor's house in Santiago didn't exist. That the lot was empty like before, and that another neighbor had filled it all with snow with a machine to celebrate a birthday.

MR: We were talking about this last night because, coincidentally, we're going to celebrate our neighbor's birthday.

NDE: And that my brother was wearing a scarf. Is it cold there?

MR: No, but it's not hot either. You dreamt something true because we were talking about birthdays.

NDE: I was at a meeting to remember a friend who died two years ago, and it was held on the top floor of a building with a view of the City, and I thought to myself, if only we had brought Mom here. There were so many places you didn't go.

MR: My trip there was short. I have to return with more time, but I have to bring my son. I cannot return alone.

NDE: You will never get to see this City in its entirety. It is way too big Where would you like to go when you come back?

MR: To a five-star hotel. Can you take me there? Hahaha

NDE: Hahaha

Ice Is Not Snow ©2010 Nicolas Dumit Estevez

December 26, 2009, Bronx, NY

Dear Mom:

I hope you are doing well when you receive this letter. I am writing to send you some of the photographs we took when you traveled to New York and to share a rough draft of the transcript I made of the phone conversations we had after your trip. Regarding the photographs, the days you spent with me are memorable because you got to see the place where I have been living for almost twenty years. When you return in 2010, God willing, I will be able to show you more of it. I think your trip was a bit rushed.

After some of our conversations, I have continued to reflect on your question: “What does art mean to you?” The answer is that I see art as a tool that has helped me understand life. In the specific case of our experience in New York, for which we declared the ten days we would spend together in the city as "life-art," art opened a space that allowed me to be aware of details that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. In other words, the day-to-day presented us with a potential for growth that we sometimes don't realize and that somehow, we can access through artistic experiences. I would like to clarify that I'm not talking about art as we traditionally know it, object-based art, but about art as a creative process that allows us to be in it, fully. This art has the capacity to let us see the ordinary—the mundane—from different angles.

Thank you so much for your visit and for sharing this experience with me. By showing the photos of the trip to others, we will be extending the memory of our days in New York City. By talking about your walks and strolls through the city, you'll be keeping alive the memory of your stay; you'll be creating art. Please email or call me when you receive the package accompanying this letter.

Hugs, Dumit, Longwood, Bronx, New York

P.S.

December 27, 2009

Mom, the postscript to this letter might end up being longer than the initial message. I didn't want to close this document without mentioning some of the many times we've both used art to address, understand, and learn from mundane situations. For example, when we collected seashells on the beach in Monte Cristi, and upon arriving in Santiago we set about gluing them with cement to one of the walls of the patio at our house in Las Colinas. I remember the minimalist look of the ivory-white seashells against the whitewashed wall. Or when you asked me to add a few words to a letter you were sending to Aunt Anissa in the capital. I asked you to draw a rose for her. You didn't agree to my idea. It was an artistic moment that never came to fruition. In any case, I was content to imagine the rose exactly as I wanted to depict it.

What about the elaborate clothes you used to dress me in as a child: velvet shorts and shirts with sleeves finished with ruffles. Weren't these props for a theatrical production or a performance? Don't think I can overlook the freedom you gave me to collect and classify stones and saints, and to transform my room into a museum of the everyday with these objects. The image of the altar I set up in a corner of my bedroom with the saints I bought with the money my uncles and cousins gave me remains vivid in my mind. Back then, religious chromolithographs used to cost about 25 cents. Talking about altars, you were able to see Pepón Osorio's La Cama at El Museo del Barrio.

I'll say goodbye now. Otherwise, this postscript risks going on almost indefinitely.

Still in Longwood

No Images above, in this piece, can be used withot prvious permission from Nicolás Dumit Estévez raful